How Trade Policies Accelerate Climate Adaptation

The Role of Trade and Trade Policies in Strengthening Infrastructure and Climate Data

The summer of 2024 brought unbearable heat, especially for retirees in China’s inland provinces. Many sought refuge in the Nanyue mountain resort, hoping for cooler air, but torrential rains and landslides soon forced them to leave. Returning to the cities offered little relief, as they faced floods, blackouts, and relentless heat waves. People found themselves caught between climate disasters, unprepared and vulnerable.

Floods and hurricanes are no longer rare—they are becoming frequent and widespread. From cyclones in the Bay of Bengal to the Camp Fire in California, and from floods in West and Central Africa to Hurricane Helene in the south-eastern US, these increasingly intense events are claiming lives, damaging economies, and threatening food security.

Even those living in “safer” areas are not immune. A warming planet means higher electricity bills and reduced productivity during extreme heat. Over time, the impacts of climate change—such as climate-related illnesses, ocean acidification, and rising sea levels—will become impossible to ignore.

While climate adaptation primarily involves national planning, international trade can play a key role in supporting those efforts. Using recent hurricane-induced landslides and floods in Nanyue Mountain, Hengyang, Hunan Province, as an example, we highlight two major challenges for inland developing areas in climate adaptation: finding shelter and accessing information. This article looks at how international trade can address these challenges and explores the role of trade policies in protecting people from urgent climate threats.

Strengthening Standards for Climate-Resilient Infrastructure

In Nanyue Mountain, residents take shelter in their homes, which are sturdy enough for normal weather but not built to withstand extreme weather caused by climate change. This summer, the rainfall in the area exceeded 302 millimeters in just 24 hours, breaking the historical record. The heavy rain was triggered by a stronger hurricane that moved inland after intensifying over warm seas.

Mr. Li, a local resident, was lucky to survive the disaster. After experiencing minor landslides three or four years ago, he built a retaining wall that ended up saving his house. Others weren’t as fortunate—long administrative processes, low awareness, and high reconstruction costs held them back. Most of the cost of rebuilding a climate-resilient house comes from design, construction, and materials. Mountain residents have basic construction skills and use local materials to keep costs low, but the lack of up-to-date building standards presents a significant challenge in designing climate-resilient houses. Without streamlined processes and materials, residents often spend more and are more likely to redo their work.

The lack of up-to-date building standards presents a significant challenge in designing climate-resilient houses.

China’s National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035 emphasized the need to update construction standards for drainage, ventilation, and wall strengths. However, progress has been gradual. Adapting to climate change requires data, but historical data is outdated, and new data is limited—especially in rural areas. Additionally, some extreme weather events are relatively new, making it hard to create standards based on their impacts.

A practical way to update standards amid a shortage of climate data is to learn from the practices of other countries with more comprehensive data and advanced risk assessment methods. For example, the European Union’s Technical Guidance on Adapting Buildings to Climate Change highlights strategies for managing climate hazards, including landslides and floods, which increasingly threaten vulnerable regions. At the same time, it is important for developing countries to strengthen their own capacity in climate risk assessment services. Trade in such services is often constrained by language barriers, geographic challenges, and limited liberalization in the sector.

Improving Climate Data Through Trade Liberalization

Information is central to climate adaptation. According to UNEP, developing countries face challenges in updating building codes due to limited access to quality data. Early warning systems also depend on the effective collection, analysis, and sharing of climate and weather data to save lives.

What powers effective data collection? At its core: devices and the expertise to operate them. These tools combine tangible goods, such as Internet of Things (IoT) devices, with intangible assets like patents and technical know-how. Sensors, for instance, offer an opportunity to strengthen data collection infrastructure. Trade in sensors can potentially make them more accessible and affordable—particularly in rural areas where they are needed most.

International trade policies can make sensors more affordable by removing tariffs. Given their dual role as information technology tools and environmental solutions, trade liberalization discussions could be pursued under the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) or the Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA). Both aim to remove tariffs on specific products classified under the HS code. However, expanding the ITA or resuming EGA negotiations comes with its own set of challenges.

Trade liberalization discussions could be pursued under the ITA or the EGA.

The ITA Expansion (ITA 2) Agreement of 2015, which extended coverage to include medical equipment and other IT-enabled products, took three years to finalize. Reaching consensus among all participants was a major challenge, further complicated by differing classifications of dual-use goods and the concerns of developing countries. While there is a compelling case for pursuing a further expansion of the ITA (ITA 3) to include IoT devices and sensors for collecting and monitoring climate data, the EGA may provide a more suitable platform for advancing this discussion.

The EGA’s critical mass decision-making approach provides a structural advantage over the ITA expansion’s full consensus requirement, theoretically making negotiations easier to conclude. Both critical mass (the share of global trade represented) and full consensus refer to the participants of the negotiations. The EGA’s clear environmental objectives also align closely with the goals of climate adaptation tools. If successfully concluded, the elimination of import tariffs would benefit all WTO members on a most-favored-nation (MFN) basis, significantly boosting trade in environmental goods. However, in practice, EGA negotiations stalled in 2016, just two years after their launch, due to disagreements over product coverage, geopolitical tensions, and diverging national priorities.

Negotiations outside the WTO framework among smaller groups of like-minded countries have seen some progress. For instance, the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade, and Sustainability (ACCTS) seeks to eliminate both import and export tariffs and covers a broad range of goods and services for climate adaptation. Although negotiated outside the WTO framework, the ACCTS aligns with WTO rules, particularly the MFN obligations (under paragraph 1 of Article I of GATT 1994 and paragraph 1 of Article II of GATS) to extend benefits to other members. Additionally, the agreement is open for other WTO members to join, providing valuable negotiation insights and a detailed list of environmental goods and services that can offer inspiration for future agreements.

Enabling Technology Transfer for Climate Adaptation

Sensors can help rural areas collect climate data, but they are only part of the solution. What’s often missing is the knowledge to integrate these devices into the broader systems they support, optimize their performance, ensure regular maintenance, upgrade them when needed, and process and analyze the raw data they produce. In short, both technology and expertise are essential to fully utilize these tools.

Unlike sensors, which can be purchased off the shelf, technology is typically transferred through licensing agreements that grant patent rights to buyers. While the protection of intellectual property (IP) rights recognizes and rewards innovation, it can also create barriers to the free dissemination of technology. The challenge, therefore, is to strike a balance between the rights of IP owners and the public interest—especially when addressing urgent global issues like the climate crisis.

Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement permits the use of technology without the authorization of the right holder, but only under strict conditions. These include case-by-case government authorization, domestic market requirements, prior efforts to obtain voluntary licenses, limitations on scope and duration, and adequate remuneration to the right holder, among others. As a result, potential users are less likely to resort to this provision, and the mechanism largely serves to protect the interest of the right holder.

Is there a way to make TRIPS Article 31 more responsive to the public interest? One possibility lies in the precedent set by the TRIPS Agreement’s amendment with Article 31bis, which allows compulsory licenses for the production and export of medicines to countries lacking production capacity. Designed to address global public health needs, it serves as a valuable example of international cooperation. Could a similar amendment, TRIPS Article 31ter, be introduced to tackle the urgent challenges of climate change?

Could a similar amendment, TRIPS Article 31ter, be introduced to tackle the urgent challenges of climate change?

Introducing such an amendment would require consensus among WTO members at the Ministerial Conference to advance the proposal, followed by ratification by a two-thirds majority of members. Historically, the process for Article 31bis spanned 16 years—from the 2001 Doha Declaration to the 2003 interim waiver, the 2005 General Council Decision, and ultimately the 2017 entry into force.

Given the urgency of climate adaptation, the world cannot afford such a timeline. A 2026 Cameroon declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and climate adaptation at the WTO’s 14th Ministerial Conference (MC14) could be a practical starting point.

A 2026 Cameroon declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and climate adaptation at the WTO’s MC14 could be a practical starting point.

Article 66.1 of the TRIPS Agreement grants least-developed country (LDC) members extended transition period for complying with IP protection and enforcement obligations. These countries are among the most vulnerable to climate change due to their economic and financial constraints, despite having contributed the least to the problem. While this flexibility allows room for development, low levels of IP protection alone are insufficient—and even counterproductive—for attracting the technology that LDCs urgently need. Incentives are essential.

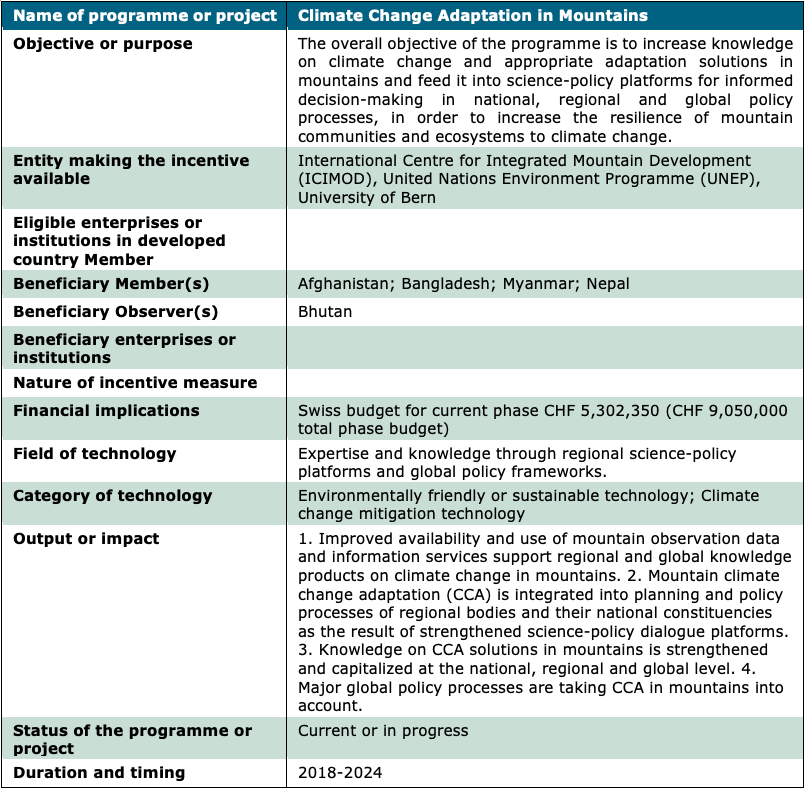

Under TRIPS Article 66.2, developed country members are committed to incentivizing technology transfer to LDCs, enabling them to create a sound and viable technological base. Although Article 66.2 does not explicitly impose notification obligations, a 2003 Decision by the Council for TRIPS requires developed country members to submit annual reports on actions taken or planned to fulfill their commitments under Article 66.2. Since 2020, over 200 reported programs or projects have been climate-related. Below is an example from Switzerland that supports climate adaptation in mountain areas within LDCs.

Source: Report on the Implementation of Article 66.2 of the TRIPS Agreement, Switzerland 2024, IP/C/R/TTI/CHE/5.

How can we maximize Article 66.2’s contribution to climate adaptation by ensuring technology is transferred to areas where it is most urgently needed? One approach could be to expand the scope of beneficiary members. Non-LDC, climate-vulnerable members—such as small island developing states (SIDS), landlocked developing countries (LLDCs), mountainous regions, and low-income developing countries highly vulnerable to climate disasters—should also be included in efforts to provide support through incentivized technology transfer.

Additionally, LDCs facing graduation in the coming years, such as Bangladesh, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Nepal, and Solomon Islands, are expected to encounter even greater climate challenges as global warming intensifies. Providing technology transfer support to these countries post-transition will be critical to ensuring their resilience to climate-related impacts.

Developed country members can take proactive steps to voluntarily include non-LDC, climate-vulnerable members in their technology transfer projects alongside LDCs. For example, in 2024, New Zealand reported a project on climate-smart agriculture that supported the installation of the first-ever livestock greenhouse gas (GHG) measurement equipment in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, and the Philippines—countries that are not all classified as LDCs. Similarly, the United Kingdom, the European Union (on behalf of Germany), and Australia have also included non-LDC, climate-vulnerable members in their projects.

One approach could be to expand the scope of beneficiary members.

Another way to strengthen technology transfer to LDCs could be to expand the scope of reporting members. Without modifying the obligations under Article 66.2, a ministerial declaration or a joint statement could encourage capable developing country members to voluntarily report their efforts in supporting climate adaptation technology transfer to LDCs in alignment with Article 66.2.

For example, China contributes nearly 40% of global green and low-carbon technology patents. Voluntary reports to the Council for TRIPS from similar developing country members on their technology transfer initiatives to LDCs could enhance transparency and embody the spirit of "reforming by doing" within the WTO. Such an approach could save valuable time, which is crucial to accelerating climate adaptation. 🌏

Last updated: 29 November 2024